When you’re learning Python, one concept that might seem tricky at first is scope. Scope determines where a variable can be accessed in your code. Understanding scope is important because it helps you avoid bugs and write code that behaves as expected. In this guide, we’ll explain scope in a simple way, covering the LEGB rule, the different levels of scope, and the keywords global and nonlocal. We’ll also include examples and exercises to help you practice. Let’s dive in!

What is Scope?

In Python, scope refers to the region of your code where a variable is defined and can be used. Think of it like a set of rules that decides where a variable “lives” and where it can be accessed. If you try to use a variable outside its scope, Python will either raise an error or behave unexpectedly.

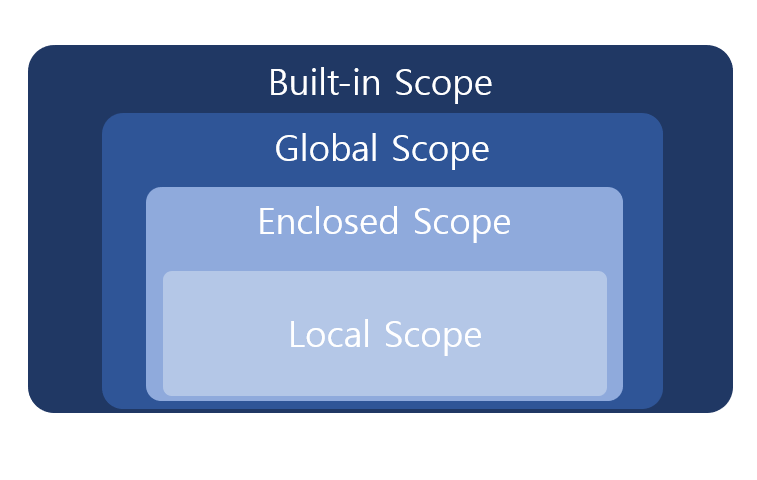

Python uses the LEGB rule to determine which variable to use when you reference a name. LEGB stands for:

-

Local: Variables defined inside a function.

-

Enclosing: Variables defined in the outer function of a nested function (used in closures).

-

Global: Variables defined at the top level of a file or module.

-

Built-in: Names that are pre-defined in Python, like len or sum.

Let’s explore each of these levels and see how they work with examples.

Part A: The Levels of Scope

1. Local Scope

A variable defined inside a function has local scope. This means it can only be accessed within that function. Once the function finishes running, the variable is destroyed.

Here’s an example:

def my_function():

x = 10 # Local variable

print(f"Inside function: x = {x}")

my_function() # Output: Inside function: x = 10

print(x) # Error: NameError: name 'x' is not definedIn this example:

-

x is a local variable inside my_function.

-

Trying to print x outside the function causes a NameError because x only exists inside the function.

2. Enclosing Scope

The enclosing scope comes into play when you have nested functions (a function defined inside another function). A variable defined in the outer function can be accessed by the inner function, but not outside the outer function.

Here’s an example:

def outer_function():

message = "Hello from outer!" # Enclosing variable

def inner_function():

print(f"Inner function says: {message}")

inner_function()

outer_function() # Output: Inner function says: Hello from outer!

print(message) # Error: NameError: name 'message' is not definedIn this case:

-

message is defined in the enclosing scope of outer_function.

-

The inner_function can access message because it’s inside the outer function’s scope.

-

Trying to access message outside outer_function causes an error because it’s not in the global scope.

3. Global Scope

A variable defined at the top level of a Python file or module has global scope. It can be accessed anywhere in the file, including inside functions, unless it’s shadowed (we’ll talk about shadowing later).

Example:

x = 100 # Global variable

def my_function():

print(f"Inside function: x = {x}")

my_function() # Output: Inside function: x = 100

print(f"Outside function: x = {x}") # Output: Outside function: x = 100Here:

-

x is a global variable, so it’s accessible both inside and outside the function.

-

Functions can read global variables without any special keywords.

4. Built-in Scope

The built-in scope includes names that Python provides by default, like len, sum, print, or int. These are always available unless you overwrite them (which you should avoid).

Example:

def count_items():

my_list = [1, 2, 3]

print(f"Length of list: {len(my_list)}") # len is a built-in function

count_items() # Output: Length of list: 3Here, len is a built-in function that’s always available in Python’s built-in scope.

The LEGB Rule in Action

When Python looks for a variable, it checks the scopes in this order: Local → Enclosing → Global → Built-in. Here’s an example that shows all levels:

x = "global" # Global scope

def outer_function():

x = "enclosing" # Enclosing scope

def inner_function():

x = "local" # Local scope

print(f"Inside inner_function: x = {x}")

inner_function()

print(f"Inside outer_function: x = {x}")

outer_function()

print(f"Outside: x = {x}")

# Output:

# Inside inner_function: x = local

# Inside outer_function: x = enclosing

# Outside: x = globalIn this example:

-

Python uses the local x inside inner_function.

-

It uses the enclosing x inside outer_function.

-

It uses the global x outside the functions.

-

If none of these exist, Python would check the built-in scope (e.g., for len).

Part B: Important Keywords

Python provides two keywords to work with scope: global and nonlocal. These let you modify variables in the global or enclosing scope from inside a function.

The global Keyword

If you want to modify a global variable inside a function, you need to use the global keyword. Without it, Python assumes you’re creating a new local variable.

Example:

x = 10 # Global variable

def update_global():

global x # Declare that we're using the global x

x = 20 # Modify the global x

print(f"Inside function: x = {x}")

update_global()

print(f"Outside function: x = {x}")

# Output:

# Inside function: x = 20

# Outside function: x = 20Without global x, Python would create a new local variable x inside the function, leaving the global x unchanged.

Here’s what happens without global:

x = 10

def try_update_global():

x = 20 # Creates a new local variable

print(f"Inside function: x = {x}")

try_update_global()

print(f"Outside function: x = {x}")

# Output:

# Inside function: x = 20

# Outside function: x = 10The nonlocal Keyword

The nonlocal keyword is used in nested functions to modify a variable in the enclosing scope. It’s similar to global, but it refers to the outer function’s scope, not the global scope.

Example:

def outer_function():

count = 0 # Enclosing variable

def inner_function():

nonlocal count # Use the enclosing count

count += 1

print(f"Inner function: count = {count}")

inner_function()

print(f"Outer function: count = {count}")

outer_function()

# Output:

# Inner function: count = 1

# Outer function: count = 1Without nonlocal, Python would create a new local variable count in inner_function, and the enclosing count would remain unchanged.

Shadowing Variables

Shadowing happens when a variable in a local or enclosing scope has the same name as a variable in an outer scope. This can cause confusion because Python will use the variable from the innermost scope.

Example:

x = "global"

def my_function():

x = "local" # Shadows the global x

print(f"Inside function: x = {x}")

my_function()

print(f"Outside function: x = {x}")

# Output:

# Inside function: x = local

# Outside function: x = globalHere, the local x inside my_function shadows the global x. To avoid confusion, try not to use the same variable name in different scopes unless you’re intentionally using global or nonlocal.

Practice Exercise: Shadowing and Scope

Let’s try a small exercise to solidify your understanding. Create a program with the following:

-

A global variable score = 100.

-

A function update_score() that tries to change score to 200 without using global.

-

Another function update_score_global() that uses global to change score to 200.

-

A nested function setup where the outer function has a variable level = 1, and the inner function tries to increment level using nonlocal.

Here’s the solution:

score = 100 # Global variable

def update_score():

score = 200 # Creates a local variable

print(f"Inside update_score: score = {score}")

def update_score_global():

global score # Use the global score

score = 200

print(f"Inside update_score_global: score = {score}")

def outer_level():

level = 1 # Enclosing variable

def inner_level():

nonlocal level # Use the enclosing level

level += 1

print(f"Inside inner_level: level = {level}")

inner_level()

print(f"Inside outer_level: level = {level}")

# Test the functions

print(f"Initial global score: {score}")

update_score()

print(f"Global score after update_score: {score}")

update_score_global()

print(f"Global score after update_score_global: {score}")

outer_level()

# Output:

# Initial global score: 100

# Inside update_score: score = 200

# Global score after update_score: 100

# Inside update_score_global: score = 200

# Global score after update_score_global: 200

# Inside inner_level: level = 2

# Inside outer_level: level = 2What’s Happening?

-

In update_score, the score = 200 creates a local variable, so the global score stays 100.

-

In update_score_global, the global keyword lets us modify the global score, so it changes to 200.

-

In outer_level, the nonlocal keyword lets inner_level modify the enclosing level, increasing it to 2.

Conclusion

Understanding scope in Python is key to writing predictable code. The LEGB rule (Local, Enclosing, Global, Built-in) explains how Python finds variables. The global and nonlocal keywords let you modify variables in outer scopes, but use them carefully to avoid confusion. Shadowing can also cause unexpected behavior, so try to use unique variable names in different scopes.

To master scope, practice writing functions with local, enclosing, and global variables. Experiment with global and nonlocal to see how they affect your code. With time, scope will become second nature, and you’ll write cleaner, more reliable Python programs!

Leave a Reply